Kathryn MacDonald

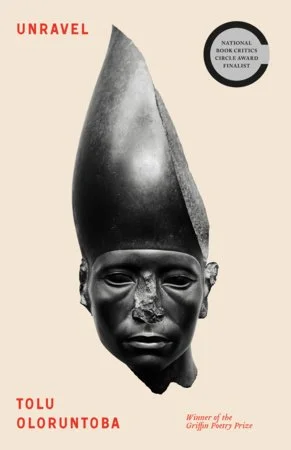

Tolu Oloruntoba, unravel.

toronto, on: mcclelland & stewart, 2025. $22.95

After sitting with Unravel for more than a month, reading and rereading it again and again, I continue to be wary of writing this review both out of anxiety that I have not grasped the depth of Tolu Oloruntoba’s intense, multi-layered poetry, and for fear of overusing the superlatives that come to my lips when reflecting on its beauty and power.

Oloruntoba’s writing is inflected with the Yoruba language and steeped in various mythologies, literary allusions, and philosophical ideas, all of which contribute to the challenge and reward of reading and rereading his work. His first collection, The Junta of Happiness, won the 2022 Griffin Poetry Prize, the judges’ admiring citation states that his poems “leave an imprint both violent and terrifyingly beautiful.” His second collection, 2022’s Each One a Furnace, explores the migration of birds as a means of reflecting on the transience, instability, and environmental concerns that shape the human diaspora. The poems in these two collections are draped in sensuous, visual, sound-rich words, rhythms, and metaphor; they set the groundwork for the poetry of Unravel and affirm that, whatever challenges it may present, reading Oloruntoba is always worth the effort.

From Unravel’s first poem, “Re-Claim,” Oloruntoba introduces a tension that will soon become familiar. The speaker, a man of the diaspora, is caught between worlds that are often represented by biblical quotes and the legacy of his Yoruba ancestors. An acolyte, the speaker quotes readily from the Bible but then considers his ancestors: “They are wrong / to trust me.” The speaker says, “I have not told them. / I have not revealed myself.” There is tension within the speaker, who is caught between worlds. The tension continues in the second poem, “Contronym,” where Oloruntoba writes, “I have raveled; have unraveled.” He asks, “Can I not be my own Antigonegonegone? / Holding a gnosis that pits me between gods / and men?” The speaker is in spiritual crisis “[b]ound to one destiny, bound for another, / ambivalent,” and self-consciously knowing all the while, “my contronyms must be a babble, / and untranslatable, to you.”

In his notes at the back of the collection Oloruntoba provides a clue to understanding the ever-present cultural tension that runs through the book. There he tells us, for example, that “A Famished Road” is a riff on Ben Okri’s novel, The Famished Road. Understanding Okri’s novel helps us to grasp the tension in Oloruntoba’s poems between the two spiritual paths that sit (un)comfortably in his work—Christian and animistic; the new and the old, the reality of those living diasporic lives. He brings this experience of spatial and temporal dis/placement to most of these poems, often making demands of his readers, as in “Ekphrasis,” which begins:

The land is helpless in its oceanic fist.

Diaphanous Aladuras in white are dogged

on their spent trip of Bar Beach where

disillusionments are acrid salt sprays

crashing into the sea.

In these five short tone-setting lines, we meet the Aladuras (Yoruba “persons of prayer”), and discover place, the touch and scent of “acrid salt,” and the sound of the sea crashing. This descriptive stanza leads to the poet/speaker “troubling the shoreline” in his “desperation,” his prayer: “My help me / was invocation.” This is an invocation that will be repeated. We learn the speaker has been “rebuilt before,” that now he prays to be reduced, to be reborn again:

Attenuate me not. Make me more myself,

a testament of krill greening my kill site,

life form profuse and boiling the shore in entry

as I cry out from my water rebirth,

and those who had believed, and waited, rejoice.

In the second part of the poem, “2: Confession, Circumfession, Contrafession,” Oloruntoba again alludes to the Bible with his plea: “As children do, I became a question // for myself…The dark made me chimera.” The section titles are important messages that provide guidance for readers. The speaker struggles, admitting “I feel guilty / of something. I just do not know what it is.” In “3: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion,” the speaker is the one being crucified alongside two thieves including a re-gendered Gestas, of whom he writes: “She was guilty / only of this: not being fawn enough. Dismas / had done what we all would, try to snap the last / ticket….” The poem concludes by reminding us of loss:

I cannot touch my friends across our plots of sky.

But the drool of our screams can see the hill

with iron, and our roots can become global

in stealth escape from centurion gazes.

In this end, our illness is awake, awave again.

Come, it says. Yes, we say.

In another poem, “Iyéwándé” (a Yoruba word for a name given to a girl after the loss of a mother or grandmother) we meet Oloruntoba’s speaker as a father. It is a praise poem, a promise poem, music, a chant, a song, and a kind of prayer. He will feed the girl, cleanse her, “teach her to walk,” teach her “what unfamiliar words mean. / [he] will kiss her on the cheek.” The poem is so rich that I hesitate to paraphrase it for fear of diminishing its powerful evocation of both love and grief. In the end Oloruntoba writes: “I will not let her die.” It is every parent’s promise, though even in this poem the speaker is conflicted, caught between the love for his daughter and the guilt he feels for his “unmourned” grandmother.

This collection is one of the most beautiful that I have read; it is a haunting rant against death. Many of the poems in Unravel fall some where between the defiance of Ginsberg’s Howl and the generational diasporic trauma of Fady Joudah’s poetry of witness. In a poem simply titled “F,” Oloruntoba writes:

Poetry may be that truce with my death drive,

surrender terms after armies within me reached

Harmagedōn. That the toxins I thus expressed

formed ornate crystals, does not make it art.

This work is to re-pare, make ready with the knife

again. Cruel man that I am, I prefer my singers

broken. No worse than those who like their poets

fragile, scared, thrumming with the terror of being

alive.

The speaker goes on to address the poet Franz Wright, offering a clue to a more thorough and allusive understanding of this poem and others on the same theme. Oloruntoba provides a number of notes like this at the end of the collection that will help readers who want to dig into Unravel’s litany of allusions and references, and what may otherwise be written between the lines. But the poems themselves are so skillfully offered and masterfully constructed that one is also rewarded for simply reading for what the surface presents, what the craft delivers, and the experience of the poems as they carry us through history, displacement, and language as they articulate what Oloruntoba has called “the unsay able [making] sense of the world.”

Kathryn macdonald’s

reviews appear in literary journals across Canada. Her poetry appears in journals and anthologies in Canada and abroad. A forthcoming collection will be released by Frontenac House in Spring 2026. She co-authored Liminal Spaces (Glentula Press, 2025) and authored Far Side of the Shadow Moon: Enchantments, A Breeze You Whisper: Poems, and Calla & Édourd. For more information: https://kathrynmacdonald.com.