Aviva Rubin

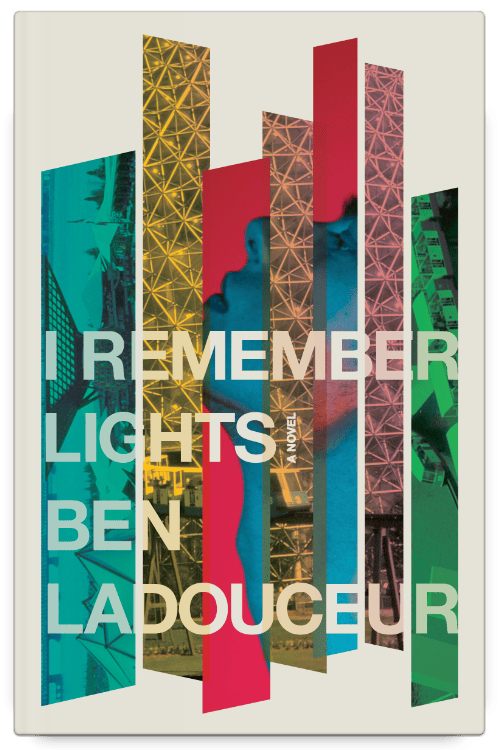

ben ladouceur, I remember lights.

Toronto, on: book*hug press, 2025. $24.95

The first thing I thought when I finished Ben Ladouceur’s I Remember Lights—aside from I need to read this again right now—was how much I wanted to find the perfect words to capture the searching, painful, moving, bold, hot, funny, unabashedly gay beauty of this glorious com ing-out-and-of-age story.

Written in first-person by a main character referred to only as “he,” the story moves back and forth between 1967 and 1977 in a gritty, shiny Montréal where raids on gay hangouts are commonplace, men are arrested, lives are destroyed, and the concept of gay liberation is on the verge of igniting. From the opening scene in a discreet bathhouse, “he” heads to a bar with the lovely, long-haired young man in the burgundy jumpsuit he has just met who dares so boldly to grab and hold his hand in the street.

The story then jumps back to 1967, when nineteen-year-old “he,” newly arrived on holiday from small-town New Brunswick with the girl he’s meant to marry, is launched into his deeply repressed gayness. As they pull into Central Station in Montreal, his girlfriend likens the journey to the wonder of travel she felt as a child: “You fall asleep on the couch or in the car, and when you wake up, you’ve been taken somewhere else.” “He” disagrees: “Where I fell asleep and where I awoke had always been the same.” But Montreal will soon become his true awakening.

Fingering his dead mother’s emerald ring in his pocket, he stands outside of a bar next to the girl he has never kissed—but is ready to propose to—when two men exit. Eyeing them, the older man says, “Pas de filles,” then translates, “no girls.” The young man lightly touches “his” waist as he passes by. In that instant, “he” realizes that his desire for men may not be a mere burden, but something shared and full of possibility.

Days after his decision to stay on alone in Montreal, “he” stands looking out at the “work-in-progress” that is Expo: “I felt like the construction site. I was a project still ongoing. I didn’t exist right now but soon I would.” Expo 67 is both a character in the story and a metaphor for a futuristic world barely yet imagined, a world of shimmering, plastic, fleeting glory in which “he” too will become himself. But as Ladouceur reveals, there are limits to this bright new world; anything gay must still remain coded, and in the shadows, even in the face of all this progress.

The story rolls and lurches between mundane struggles—finding work delivering and picking up diapers, securing a place to live where he feels more or less safe, making friends he can trust—and a vividly and viscerally described sexual awakening. After his first-ever hookup in the woods by a river, he thinks, “The world was mine and I was its. I fitted into the earth perfectly, like a stone yielding to the suck of the mud it has landed in.” The certainty and exaltation in this description is a gift Ladouceur gives both his main character and the reader.

The relationships “he” forms, tender and tentative at first, capture a multitude of tensions, risks, self-doubt, and homecomings. Honoré, his Québécois lover, lives a self-hating double life but still offers a haven far from the shared living room of the kind-but-judgmental Portuguese Maria, and her daughter and grandson Tomas, with whom “he” first lives. Étienne, an intellectual from France, becomes his first roommate and later dear friend. In a painful scene, “he” helps Étienne straighten his hair with a toxic, burning salve required for his job at the French pavilion, where he is the only Black man. And then there is Tristan, a long-haired Welsh free spirit (at least while he is away from England) who becomes his first love. Over those early months in Montreal, both a community in which “he” belongs, and a fledgling confidence in his identity as a gay man, begin to take shape.

Ladouceur’s prose, filled with moments of discovery, pleasure, connection, and humour, are poetic and clean, never flowery or overwritten. He skillfully forces the reader to sit in the discomfort, precarity, and ever-lurking danger “he” faces throughout. In one of the novel’s most devastating scenes, “he” is at Expo’s amusement park, La Ronde, and runs into Tomas. They are chatting happily when Tomas’s mother arrives and begins screaming, implying that “he” is a pedophile, and threatening to call the police or kill him herself. “For a moment I could not speak. Once I could, I said to her, ‘I’m sorry.’” In these two words, the author captures the plague of self-loathing and shame that pollutes so much of the gay experience of this time and place.

In the spare and exquisite prose of I Remember Lights, there are often more hard lessons than wins. Despite this, the novel always lands on hope by shining light into the intimate spaces. As a reader, I was there with “he” in the elation and comfort of friendship, the thrill of finding love and a sense of belonging, and the constant heartbreak and ignominy of a world rooted in violent judgment. I felt grateful to know that a better, though always precarious, future awaits.

AVIVA RUBIN

is a Toronto-based writer of memoir, essays, social commentary, and fiction. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, the Globe and Mail, Chatelaine, Toronto Life, and Zoomer, as well as numerous anthologies. Rubin is the author of the memoir, Lost and Found in Lymphomaland, a harrowing and funny trip through a cancer diagnosis and treatment. WHITE is her debut novel.