Matthew Boylan

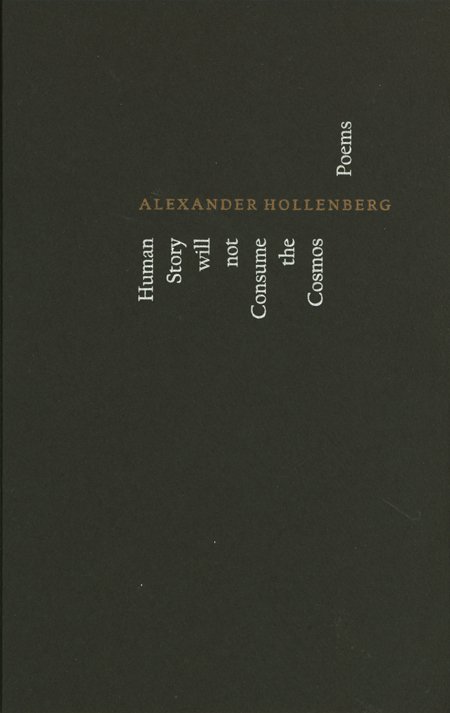

Alexander Hollenberg, Human Story Will not Consume the Cosmos.

Kentville, NS: Gaspereau Press, 2025. $24.95

Hamilton, Ontario-based poet and professor Alexander Hollenberg’s debut book of poetry, Human Story will not Consume the Cosmos, is an ode to living language. It is a poignant, funny, conscientious, and deeply readable collection that hits on a diverse range of topics and themes—from the galactic universe to the banality of mortgage payments, from the insidious creep of technology into our lives, to the ritual of fishing—all the while affirming a vivid enthusiasm for life and an honest, cerebral perspective on living it.

The book is divided into five eminently re-readable sections, each containing poems that speak to different themes. In “Spruce Crow” we encounter a crow and a squirrel, contemplate wild raspberries and blackberry thorn, and bear witness to the life and death of a famous groundhog. Hollenberg transforms the mundane into beautiful cosmic rhapsodes, observing the crow’s “new cosmos in the ink of her wing,” or as a falling squirrel (named Bernard) becomes “an acrobat choosing orbit over earth.” The poems in this section evoke the living language of the “inchoate raspberry” and eulogize the eternal shadow of Fred la marmotte, for “there will always be shadows as long / as there is sunlight in February.” In “Cosmic Bop” the tangible, suffocating concerns of modern life such as “mortgage payments, / [a]mortized over eons,” are quelled within the simple reminder to “[t]ell yourself you are made of stardust.” With irony fully engaged, the speaker eases the pains of modern home ownership by assuring us that we, after all, “are untraceable—collection agencies will search / but only find atoms, not worth the bounty.” Poems about an ice storm, a road trip, and the delicate beauty of salmon round out “Spruce Crow” as Hollenberg introduces us to his world and brings it to life.

In the next section, “Cod Jigging near Twillingate,” Hollenberg writes about nostalgia and about fishing. Transmuting his experience into vivid imagery of “[t]he slow seagull squeak / of the dock in the breeze” and “cottage-core top 40” while meditating on the “physics of / nonhuman poetry,” we are welcomed into a meditative reflection on experience, for this section is largely about story itself. In a boat with his father Hollenberg writes that “[w]e no longer search for new stories, settled instead / to hear the old ones over,” and yet it is these old stories into which the new are woven; the experience of “story,” to Hollenberg, becomes the framework of these poems. Through meditation, revitalization, and seeing the universal within the particular, the poet ponders how “a notion of yarn / could empty an ocean,” or how, in a dream about Gordon Lightfoot we can connect across space and time: “From you at the top of your mountain / to me on mine is the measure of breath.”

In “Children of Atlantis” Hollenberg writes of memory and the future, of the ever-changing world and the traces it leaves. There is a distinctly Canadian feel to these poems, with nods to ‘80s and ‘90s touchpoints such as “Hudson’s Bay catalogues scotch-taped to the wall” or the scent of the “rayon wall you hit walking into BiWay,” that will evoke fond memories for us aging Millenials. A personal favourite here, “The Stair Lift,” is founded on the simple premise of an old contraption, now defunct, whose image carries with it many memories for the poet. The ending—“letting the ghost linger / at the bottom of the stairs, / not raising her back to her room”—is poignant and evocative of how everyday inanimate objects can carry our memories, and how poems themselves can deliver us from one time and place to another. Within all these memories, and these poems, Hollenberg creates space to “harvest cause from the cosmos,” creating new roots, new paths from which to forge meaning in the wild irrationality we call living.

In the next section, “The Human/it/(y)/(ies),” Hollenberg writes of a life of learning and teaching. The poems here, many of them rife with humour, call upon lodestars like Billy Collins, James Joyce, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and skewer the absurdity of Zoom calls and the angry dude at the campus Tim Hortons loudly lamenting the absence of “any fucking hashbrowns” on the first day of his post-pandemic return to campus. These poems are full of life, wit, a love for literature, and the project of sharing that love with others.

The capstone section of the collection is “Human Story will not Consume the Cosmos, or, Thirty Ways of Looking at the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART)” a 30-part long poem which conjoins the universal and the particular and all things in between. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test—a 2021 NASA space mission testing our ability to manipulate asteroids—forms the framework of brotherhood (both literal and figurative), politics, time, poetry, and myth. From “stars and dust and celestial puffs” to “a half-inning of mediocre baseball,” the poem is a perfect encapsulation of the collection as a whole, touching on many of the topics and themes explored in the previous sections. Here, the poet brushes the mud off the stones of this world (and others)—the metaphorical asteroid redirecting itself across space and time, as “when the meteor screams / across the sky” we find that “[t]here is no difference / between a poet and an asteroid”—ending the book with a pan-psychic prayer for a universe that is “common in the way / grief and stone are common.”

Throughout this impressive first collection, Hollenberg asks whether accepting the parataxis of living in the world could “at least allow for the possibility / that human story will not consume the cosmos.” After all, it is only in the exhaustive, confident nature of analogy that human story might perform such a feat. In these poems, the effort to explain away all things, or “why things always / have to be other things,” is not about making life perfectly intelligible, but about existing in a world of living language where experience and interpretation allow wonder and possibility to flourish in the inexplicable gaps that comprise metaphor and analogy. Human Story will not Consume the Cosmos is the summation of a poet’s discerning, delicate eye and keen imagination. Thankfully, writers like Hollenberg craft the meaningful stories and moments that can help define our universal experience and guide us along our own respective journeys through space and time.

Matthew Boylan

is a writer and graphic artist from Guelph, Ontario. In his free time he likes to read, write book reviews, and play chess. He enjoys experimental forms and content. His most recent review is published in The Ampersand Review. He is a fourth-year Honours Bachelor of Creative Writing & Publishing student.