Shaylyn Schwieg

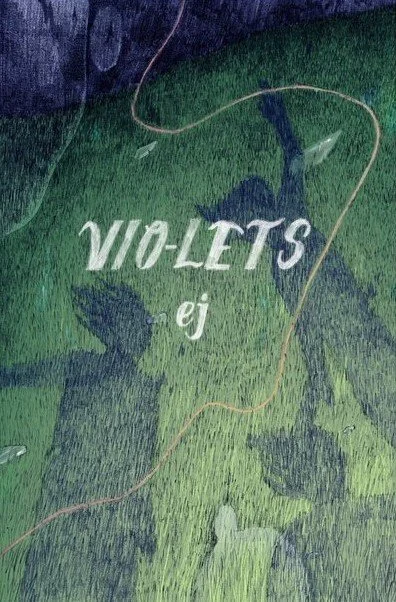

EJ Kneifel, Vio-Lets.

Toronto: Anstruther Press, 2023. $10.00.

In EJ Kneifel’s VIO-LETS there is a sense of slipping through the text. Each line flows into the next, each piece of lyric prose builds on the others, telling the story of three boys. The flow of the writing is engaging and leaves the reader chasing the next line to grasp hungrily at the next part of the sentence. The flow is also enhanced by the lack of capitalization throughout the entire piece. The lack of distinction makes the text seem all as one; even though punctuation is used all the words appear uniform, or equal.

The chapbook captures youth, wonder, and feeling. The speaker’s phrasing in much of the text helps create this as seen in the following passage:

we whoop for the dark as our usbodies leave us. we swim in it, race, little / always ahead. […] big says / when birds sing at the wrong time it reminds me of europe. leaving little / and me to wonder about where big lives. not where he lives, but where he / lives. it’s a way of speaking, you know?

The wording like “usbodies” or emphasis on “but where he / lives” rather than expanding with explanation feels young and helps to create the wonder.

Sometimes, it is as if these moments are approached with the eye of an observer—the knowledge and introspection of looking back—as in “Origin Story’s” ending “i don’t know, that’s just how it sounds, as we did what any boys / would, with any arms all hairy like fruit. we called ours what wasn’t, our / hunger so loud we were going.” It instills a feeling of nostalgia. Looking back fondly on the adventures of youth, encapsulating these moments in many ways as the poems seem to represent the present through the in-the-moment action and feelings of the characters but also represent the future thoughts of the speaker. It deepens the experience. The reader slips not only through the writing itself but through time and memories as well.

The voice of every piece is carefully curated to catch every repetition, every withheld explanation, in a way that mimics speech—like in “little naps while i hum, / while i hum[,]” and “when we first learned to skate we pushed for so long that we carved out a / river. we couldn’t go in cause little’s hair wasn’t long enough,” and “what are you doing up there? we ask / him with nuts in our cheeks. i’m trying to catch up to roger, says little.” Everything is blended into the speaker’s retelling. There is no use for quotation marks here. This also creates a sense of retelling and oral storytelling and builds on the nostalgia of the work.

Violets and the colour violet make their way into many of the pieces, slowly becoming a feature to call on. Sometimes it is invoked with flowers in a hand, sometimes in the colour of one’s eyes, and sometimes it is a reference to change. It is hard to pinpoint the motif created, but it may be a show of great feeling—regardless of good or bad—like passion. Something felt deeply—so that when eyes go violet there is the introspection and curiosity building as when “little says the moon will be full tomorrow and i understand […] would you go if you / could, he asks, eyes purple as stars, and i laugh because that’s just big in his / mouth. he says it isn’t the same as going out far, it isn’t, it’s up, and i feel / my bones pull out indigo.” Kneifel expertly captures a complex paradox: the beauty of childhood, the room to ask and ask and ask along with childhood’s downfall as we learn and learn and learn.

Shaylyn Schwieg

is a writer and reviewer from Brampton, Ontario. Currently, she works as the Events and Communications Intern at The Ampersand Review of Writing & Publishing, and studies at Sheridan College—attending its Creative Writing & Publishing Program. She enjoys exploring different genres and basking in the beauty of others’ writing. She is a proud member of the queer community, passionate about mental health awareness, and a strong advocate for environmentalism; all of which tend to be featured in her writing.