Marcus Medford

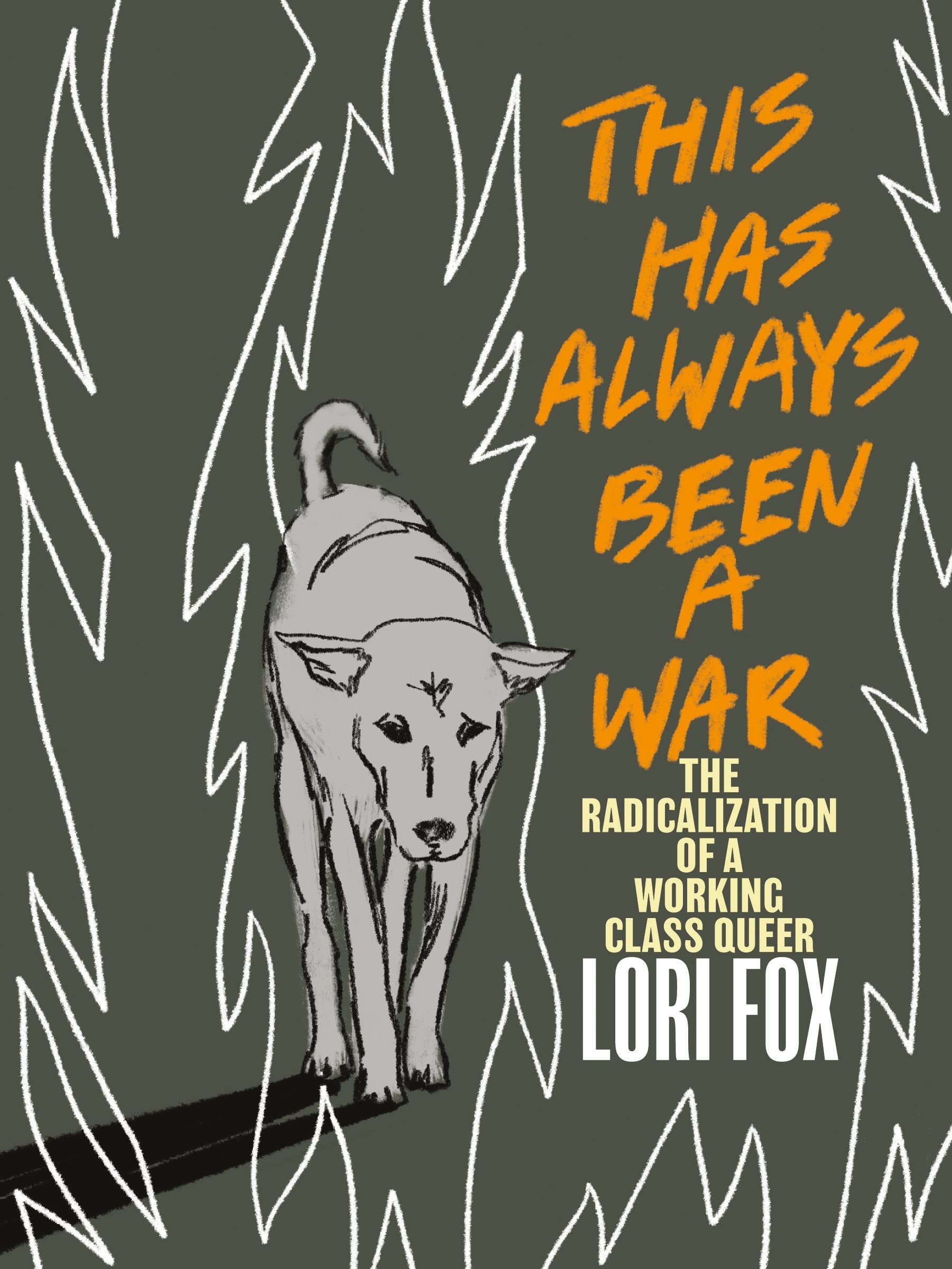

Lori Fox, This has always been a war: the radicalization of a working-class queer.

VANCOUVER: ARSENAL PULP PRESS, 2022. $19.95.

A good piece of art is one that makes you think, elicits powerful emotions, and leaves an impression even after you’re no longer experiencing it. Lori Fox’s collection of essays, This Has Always Been a War: The Radicalization of a Working-Class Queer, does exactly that.

The book is a scathing critique of capitalism that argues that capitalism has morphed beyond an economic system into a malevolent force that’s infiltrated every aspect of our lives. To use Fox’s words, “Capitalism is not simply an economic system; capitalism is culture. Specifically, capitalism is our culture. And under capitalism—within our—working-class bodies are property.”

Fox is a queer non-binary writer and journalist based in Whitehorse, Yukon. They’ve also worked as a fruit picker, bartender, a labourer, and a bunch of other jobs. This unique cocktail of life experience informs their writing and helps establish credibility.

One of their most popular essays is an opinion piece that was published last summer in The Globe and Mail, titled “I’m one of the service workers who left the restaurant industry during the pandemic. Serve yourself.” That piece and Fox’s book are based on their life experience, resulting in writing that is raw, well-researched, snarky, and combative (but in the good way that punches up, not down).

One of the things I’ve enjoyed about reading Fox is the consistency of their voice. From the eleven essays featured in the book, to their Tweets, to the copy on their website, there’s an authenticity to the words that makes them ring true, even when I disagree.

Either they’ve mastered their brand voice or it’s just an example of what Fox calls “radical vulnerability.” Fox believes that only through radical vulnerability can we truly be honest with ourselves and others, and effect change. This assessment isn’t me editorializing—it comes straight from their website. After reading This Has Always Been a War, it’s clear that Fox employed that same strategy of radical honesty and pointed criticism putting the collection together.

In the opening essay of the book, Fox details an incident when they were sexually assaulted while working as a server at a bar. I was shocked. But it was far from the last time I’d react that way as I read about Fox’s life.

Fox describes the book as “a series of dispatches from the combative front lines of our present-day culture.” It was language like this—“dispatch,” “combat,” “front lines”—that piqued my curiosity. I was struck by the word “war” in the title in particular.

War is a dark, loaded word that shouldn’t be taken lightly. To me, a war is a large, destructive, multi-pronged, near-constant state of fighting between sides who refuse to agree, where one is trying to control or destroy the other. The consequences of wars have the power to shape the world.

Thousands of kilometres away, there’s a real example of a war raging in the form of Russia and Ukraine. During the first few months of fighting, I was learning new details about the war and seeing footage of the devastation nearly every day.

War was also used as an analogy to describe how COVID-19 impacted society and how we’re dealing with it. We’re at war with the virus. Like a war, the pandemic affected everyone directly or indirectly, forced us to reorder society and I suspect the pandemic will leave a lasting scar.

War is devastating and all-consuming, so, it was a high bar for Fox to meet if I was to be convinced that our relationship with capitalism was actually a war. The idea was provocative, but was it true?

That question lingered in the back of my mind as I read the book and in the interview I had with Fox. Fox explained that they chose the title carefully and based it off of what they described as an active “social combat zone.” The essays are full of examples, from their own life and in general, laying out their argument that capitalism subjugates, often pitting groups against each other, in order to sustain itself.

There are explicit examples of how this power struggle unfolds in practice. For example, in one essay, Fox details the internal battle between front-of-house and kitchen staff at some bars and restaurants over dividing tips and scheduling. In some cases, staff have to fight each other (not physically) and play favourites to try and ensure they have enough money.

In this situation, and others like it from the essays, Fox points out the power imbalance between the parties.

Other examples are what Fox says are “passive acts of violence” against the working class. They explained that the acts are passive because they’re widely accepted by a majority of people because wealth can shield people from the realities of violence or because violence has been normalized for middle-class people to the point where it doesn’t seem like violence; it’s just the way things are.

Fox talks a lot about the time they spent homeless and the things they learned from that formative experience.

“It let me unpack all of the layers and all of the ways that capitalism, patriarchy, racism and classism interconnect to form this shield that lets rich people, even middle-class people, feel like everything is fine, even as they’re seeing things that are terrible,” Fox explained.

Patriarchy, racism, and classism—the unholy trinity—are the three pillars of capitalism, Fox argues. The book highlights that the passive acts of violence particularly affect society’s most vulnerable groups and have the power to shape their experience.

In the essay, “Where the Fuck Are We in Your Dystopia?,” Fox criticizes fellow Canadian author, Margaret Atwood, and her critically acclaimed-novel-cum-TV-show, The Handmaid’s Tale, for being exclusionary to some members of the LGBTQ community. In that same chapter, Fox talks about the depictions of women, people with disabilities, people of colour, and the LGBTQ community in the fantasy/sci-fi world, noting that they are often poorly represented if they’re included at all.

It’s almost as if Fox had a crystal ball and anticipated all the outrage that would ensue after the release of The Little Mermaid, House of the Dragon, or Rings of Power, around the appropriateness of these equity-seeking groups having roles in these made-up worlds.

“Every little act, whether intentional or not, makes us a little less than we were, than we would have been. It takes something from us. That’s what patriarchy is. That’s what capitalism is. Taking from the many to empower the few.”

Fox makes the argument that capitalism is a kind of soft determinism. This isn’t something they said explicitly, but after reading the book, that’s the conclusion I came to. And Fox seems to agree. Capitalism, as Fox sees it, works on a sink-or-swim philosophy. You either opt in and play the game, or you die: “If you can’t stop swimming or you’ll drown then is swimming really a choice?”

That comment stuck with me, and it made me angry. The way Fox talks about capitalism feels less like explaining an economic system and more like outlining the rules of a cruel game. And they spend almost the entire book outlining how these rules make the lives of working-class people, especially marginalized people, worse.

As I wrote this article, the government of Ontario was in a bitter labour dispute with members of the union representing educational support staff (like janitors, secretaries, Early Childhood Educators) over wages and working conditions. The government passed legislation to make striking illegal for union members and would hamper their ability to negotiate an improved deal. It’s an ugly situation.

And one that’s made worse by the fact that education is a woman-dominated industry whose workers can’t get a raise. Meanwhile, the Ontario government raised wages for police and firefighters earlier this year by over 2 percent. These are fields that are 78 percent and 97 percent male-dominated, respectively. And earlier in the year, large grocery chains were accused of price-gouging or “greedflation,” for making huge profits throughout the pandemic by clawing back hero-pay for front-line workers, and lying about the true cost increases in order to get more money from Canadians struggling to cope with inflation and the rising cost of living.

Initially, I thought that This Has Always Been a War was the story of Fox’s radicalization; detailing the experiences and reflections that led them to adopt the view that we are in constant clash with capitalism. And I think it is.

But I suspect the book was also given its title because one of its goals is to radicalize its reader. Now, I understand you have to be careful using that word given the political climate we’re in. That said, it feels accurate.

Reading the book made me angry, and thinking about the implications of Fox’s argument or seeing them play out in real life made me angry, which is a good thing. Because if it didn’t make me angry, I wouldn’t have cared enough to write about or talk about the issues Fox addresses through the essays.

The first step in addressing any social issue is recognizing that there is one. Only after naming the problem can one start assessing the scale of the issue, then coming up with a plan to address the issue and putting it into action. Fox does some of that legwork for the reader. This Has Always Been a War is a call to action and attention rather than a call to arms.

The book is not for everyone; the sexual assault mentioned in the first chapter sets the tone for what is a challenging and at times uncomfortable read. But this is a big and important topic that we shouldn’t shy away from, and for that reason, This Has Always Been a War: The Radicalization of a Working-Class Queer, should be considered required reading because it’s implications affect us all.

marcus medford

is a third-generation Canadian, whose grandparents came to Canada from Trinidad and Jamaica, and is currently based in Toronto. Marcus works as a freelance journalist for ByBlacks.com, New Canadian Media, The Edge, and CBC. Marcus, also known as Mars The Poet, is a two-time TEDxUTSC performer, and the author of the poetry collection Book of Mars.