Jacob Alvarado

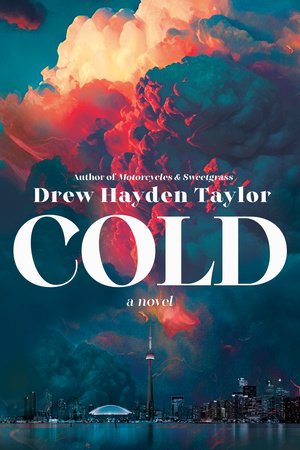

Drew Hayden Taylor, COLD: A NOVEL

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2024. $24.95

In its insightful conflation of horror, comedy, crime thriller, and character drama, Cold is a riveting blend of contemporary storytelling and Indigenous folklore. Plumbing the depths of abandonment, ambition, cultural identity, and much more, Drew Hayden Taylor expertly guides the reader through a blizzard of complex subject matter with an intelligent new novel that never ceases to engage or entertain.

Alternating between the perspectives of its three leads—journalist Fabiola Halan, hockey player Paul North, and Professor Elmore Trent—Cold begins as a series of fascinating and increasingly interrelated character studies. From a plot perspective, geography (and specifically Toronto) is the first thing to unite all three threads. Fabiola, who miraculously lived through a plane crash in northern Ontario, arrives as part of a book tour promoting her survival memoir; Paul is in town for an IHL (Indigenous Hockey League) tournament; and Elmore teaches Indigenous Studies at a local university.

But proximity isn’t the only thing that unites our main cast. As they all wrestle with different kinds of unresolved trauma and loss, the three leads of Cold gradually cross paths and overlap with one another in the lead-up to a tragic, gruesome murder that bonds them inextricably. Without giving too much away, it becomes increasingly apparent that this killing is not the first of its kind, and that the monstrous, unbelievable nature of the killer means that stopping them will take more than a traditional investigation.

At this point, it’s important to clarify something about the tone that Cold sets for the reader: Taylor states in the acknowledgements that this project was originally a film script and so, almost like a Marvel movie, the novel balances darker, violent elements with banter, wit, and the occasional laugh-out-loud moment. Consider a scene towards the beginning of the book in which Elmore fails to curry favour with his wife when he insists:

“My universe has you in it.”

“Your universe also has that young lady, whoever she may be…Elmore, your universe is getting a little crowded.” People at nearby tables were beginning to look their way. More than the lamb was heated and spicy.

While the comedy in Cold undoubtedly increases the book’s entertainment value, the novel’s tone is also vital to its accessibility. In a January 2024 interview with The Peterborough Examiner, Taylor explained that he deliberately crafted Cold as “something fun, scary and interesting that also provided some insight into Indigenous life that non-Indigenous readers will learn from and Indigenous readers will be reminded of.” Particularly in its slower, character-based moments, the book’s humour helps to bond the reader to a character like Elmore, allowing us to become endeared to his plights and engaged in the complexities and traumas of his life (including his residential-school-induced abandonment issues).

Moreover, the characters’ respective mixtures of surface-level flaws and deep-seated pain help to imbue the novel with a sense of depth and intrigue that reflects the murder mystery at its heart. For example, Paul’s predicament, much like Elmore’s, is a combination of bad choices and tragic circumstances. While much of his loneliness and his feelings of abandonment come from his reckless lifestyle and poor decision-making, Paul, who is Anishnawbe, is revealed to have been “othered” in childhood by a white schoolteacher who believed that athletics were Paul’s only option. Similarly, while Fabiola may not be an Indigenous woman, her struggle to adapt to her adopted white family as a child, and the frequent questioning of her cultural background by other characters throughout the novel, suggests a life of perceived “difference” that has forged her tough exterior and fuelled her thirst for achievement.

While not the only theme in Cold, the repercussions of cultural assimilation faced by each lead character are vital to the novel’s central meditation on the consequences of cultural disconnection. This is explained beautifully by Elmore in one of the novel’s most sobering statements:

Well, I’m diasporic in my own country […] I’m Ojibway […] I was raised in a residential school, and don’t really have any attachment to my home community. My parents are dead. My wife is white. I’m playing politics in a largely white educational system. I prefer filet mignon to moose. It seems I have excelled at living the Canadian dream. I have been called an apple so many times […] Red on the outside, white on the inside.

Packed with layered thematic material and thrilling commercial appeal, Cold is a skillfully designed whodunit whose suspenseful pacing, chilling kills, and shocking plot twists make it a worthy addition to the Canadian murder mystery canon. But while its success as a work of genre fiction is not to be discounted, Cold achieves its greatest victory by finding ways to challenge its readership. Creeping from dramatic realism into urban horror, by the time it approaches its ending, Cold itself undergoes a radical transformation that will have readers desperately flipping its pages to reach its pulse-pounding conclusion. Hopefully, when it comes to its efforts to reframe the narrative surrounding cultural identity in Canada, it will transform its readers, too

Jacob ALvarado

is a writer, poet, and Executive Assistant for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. His book reviews can be found in The Ampersand Review of Writing & Publishing, and his debut poetry chapbook, I Can Make It All Up To You, is forthcoming from Knife | Fork | Book.